Ray Daniel Wolf,

U.S. Army Air Corps

My story begins in October 1940, when the US initiated the draft prior to our entry into World War II. The Selective Service assigned numbers to each eligible male. The Director of the Selective Service (a two star General) drew slips of paper out of a “fish bowl” in Washington D.C. Induction into the service was based upon the order in which your number was drawn.

I had not been particularly lucky to that point in my life. I was born in Iowa in 1918, the second of four brothers. We moved early in my life to Nebraska where Dad had a large farm. I attended a one-room school and loved to read. I think I read every book in the school’s library. Our family was forced from the farm during the “dust bowl” when for four successive years we planted but all the crops burned up.

We arrived in California with the shirts on our backs. I remember a farmer allowed us to gather fallen fruit for one meal. Our family made its way to Arcata in 1936. We made our living on a small dairy farm. After school I had to leave my friends and go home to help with the chores. I had to take care of some of the animals and milk the cows. It wasn’t until my senior year that I was able to participate in sports. My track coach/civics instructor told me “Ray you are on both the scholastic rolls and on the track team. You are just what West Point wants. If you wish, I will get you an appointment to West Point.” I told my instructor I don’t know anything about the military, but I have two uncles who were in the US Army during WWI. One of the uncles had been gassed and both uncles advised me not to go into the US Army. Little did I know then, that six years later I would be in the US Army Air Force!

My draft number was one of the lowest numbers drawn. I expected I would be drafted into the US Army after 1941. I did not have a strong urge to join the Air Corps and since I was raised in Nebraska, where there weren’t many swimming opportunities, I couldn’t swim very far, and I could visualize the Navy ship in trouble a mile or so off shore. So I by passed the US Navy and the US Marine Corp. I had never been in an airplane nor did I have any strong longing to fly. But I thought the pay would be better in the Air Corps. At that time, the monthly pay for Army soldiers was $21.00 per month but it was used for various things so that you actually received only $6 or $7 cash.

You had to be very physically fit, have two years of college, and be under 24 years of age to qualify for Aviation Cadets in 1940. I was physically fit and I was 23 years of age, but I only had one year of college. In lieu of the 2 years of college, you could take a 3-day exam on 9 subjects. Passing the 9-subject exam was considered the equivalent of completing a 2 year college education. I had only taken 7 of the 9 subjects. I had not taken Ancient History or Geometry. I tried to study up for these two subjects, but I only had one month after work for such study. Luckily, I did well enough in 7 subjects to overcome my poor results in the two unstudied subjects. When I passed my physical at Hamilton Air Force Base, California without too much difficulty I was accepted by the Air Corps. About this time, the US Army tried to draft me, but held off because of my acceptance by the Air Corps. So, approximately 6 months after the “fish bowl” drawing, I was in the US Army Air Corps as an Aviation Cadet. I had a lot to learn about the military and flying!

I reported to the Air Corps on April 1941. Robert Dethlefson, a fellow Air Cadet, described his initiation into the Air Corps in his autobiography on this web site. I have the same memory of my first day of receiving a friendly greeting outside the front gate, followed closely by “hazing” after passing through the front gate at Cal-Aero Academy, Ontario, California. The academy was commanded by Captain Robert L. Scott, who later wrote the book, “God is My Co-Pilot”.

I will not forget the first day after my arrival. We were lined up in a single line of about 80 cadets. They told every other man in the line to take one step forward. Then, they told us to look at the line ahead or behind us. That was the number of people they intended to “wash out” or eliminate from the Aviation Cadet Academy. True to their word, eliminations were a regular occurrence during our primary and basic training.

By the time we reached Fort Stockton for our advanced training, the elimination process was completed. There were only about 40 Aviation Cadets left. Rob Dethlefsen and I were in the same flight during basic training at Cal-Aero and neither of us washed out.

My first flight in Primary was a good education for me. My instructor said to me, “You haven’t been in an airplane before, have you?” When I replied that this was my first airplane flight, my instructor said, “Just relax and enjoy yourself.” So, I did. Halfway through that flight, the instructor said “You have the airplane”. Our communications were one-way; he could talk to me, but I couldn’t talk to him. I was never so scared before! I grabbed the controls and didn’t know what to do with them. I soon found out the airplane flew better without my assistance!!!

I soloed in a little over 10 hours. I felt I was not prepared to solo but I knew you would be “washed out” if you didn’t solo before having 12 hours. We had been shooting landings and takeoffs. After about the 3rd or 4th such landings, the instructor had me stop the plane. He got out and told me to take the plane around in the traffic pattern for a couple of times. Only then did I realize that I was on my own!

My first time in the air was traumatic. I asked myself, “What am I doing in the air by myself?” My first landing was somewhat mechanical, but the next landing was fine. The rest of Primary was a constant learning process but I now had some confidence in my own abilities.

My recollection is that each day consisted of flying for half a day, ground school one half day and marching in our spare time. I was glad I hadn’t joined the Army where marching was much more time consuming.

In Basic Training, we changed from the double winged, fabric covered Stearman to the BT-13. The BT-13 landing gear was wider and it had a canopy which could be opened or closed. I had no trouble soloing in Basic and all was well until my first check ride. My previous instructor had us always taxi with the canopy open so we could see better. My first ride in Basic was with a 1st Lt. USAF pilot on a Monday morning. I had no sooner started to taxi than the 1st Lt. hollered, “Shut that damned canopy.” From that point on, almost nothing that I did pleased him. I flunked the check. I was scheduled for a recheck a week later and passed satisfactorily. It turned out that the 1st Lt. who failed me had a big weekend before the check and wasn’t too happy to be in the air.

Just a week before completing Basic Training, I went to a dance on the weekend with some Hollywood starlets. After the dance, I started to return to the airbase but was very sleepy (6 AM on Sunday). I turned the radio on, opened the windows and tried to stay awake. I was in a 6 lane highway with no middle island. In spite of my efforts to stay awake, I fell asleep, crossing all six lanes of traffic. I hit a tree on the opposite side of the road right between the headlights. My chin broke the windshield, my chest broke the steering wheel and my knees bent the dash board. I passed out so they took me to a hospital. I was released back to Cal-Aero on Tuesday, but I could hardly walk. My instructor said, “Ray you can’t fly but I will fly for you with you in the back seat.” I gratefully accepted his offer. So, I spent the last hours of Basic sitting in the back of the BT-13. My car, incidentally, was sold for junk!

Luckily, my knees recovered by the time I started Advanced training in Stockton AFB. I soloed, did night flying and cross country flying, instruments and formation work without any troubles. I finished flying on Friday, December 5, 1941. There were rumors that some of us would be sent to South America to fly some of their airliners after graduation.

On Sunday, Dec. 7th, about 10 of the Aviation Cadets, including me, were having breakfast at a downtown restaurant. We heard the radios telling us that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor and that we were to return immediately to our base!

On Monday morning they called our class to attention and told us that seven of us had to have an operation before being commissioned. We had cysts that had to be removed. The Cadets who did not require surgery were divided into two groups. Aviation Cadets whose last names started with A to O were going to North Africa. Those whose last names started with P to Z were going to the South Pacific. So much for South America!

Later that day, a Lt. Colonel (I thought a 2nd Lt. was next to God) talked to each of the seven cadets with cysts separately. He told us that unless we agreed with the planned operation, he would Court Martial us. However, the Lt. Col. also said that since our commissioning would be delayed by the surgery, we would be made instructors at Stockton AFB after the operation. The USAF had found that the cysts could become infected after some hard aircraft landings. I readily agreed to the operation since I certainly did not want an infected cyst. Each Cadet underwent a different surgical procedure to try and determine the best treatment. My procedure must have been good since I was one of the earliest to leave the hospital. We were commissioned as 2nd Lt. Pilots about the middle of January 1942. That’s how I became an instructor pilot.

Here are some excerpts from Rays log book showing his training to become a Flight Instructor. Just click on an image to see a larger picture.

After a week or so of flight instructor work, I decided to marry my childhood sweetheart, Dot. I went to my boss (a 1st Lt.) and asked for a Saturday off to go to Eureka to get married. The 1st Lt. said, “There is a war on and I have to work so you have to work.” Not to be deterred, I called Dot up anyway and asked her to marry me. I told her that if she could get to her Aunt’s place in San Francisco at 6 PM on Saturday, we could elope to Reno and be back by Sunday evening in time to go to work. Dot agreed. So we met in S.F. that Saturday. It was a rainy and snowy and the main road was under about 6 inches of water near the Sacramento River. Once we climbed the Sierra Nevada Mountains it was snowing. The car started to slip and slide, so I got out in my new USAF uniform to put chains on. We finally arrived in Reno about 4 AM. We joined the line to get married (there were about 10 couples in line). Each couple, after being married, signed as witnesses on the following couple’s marriage certificate. We returned to Stockton AFB Sunday afternoon, and I flew on schedule Monday morning.

We stayed in a motor court for about five days. Luckily, we found a little apartment (two rooms in a large apartment house). While we lived there the US Secret Service apprehended a German spy in our building. He was using musical notes to code his messages.

I enjoyed being an instructor at Stockton AFB and in assisting the war effort. TheUSAF was critically short both of pilots and planes in 1942-1943. Each instructor had five Aviation Cadets to train in the Advanced Trainer (AT-6). It was a good plane with a good engine. It had never “coughed out” on me during any of my training with the Aviation Cadets. It was a little tricky in the landing roll - the tail wheel could be bumped out of position with a resulting “ground loop”.

Every Aviation Cadet had to solo in the AT-6 aircraft. Very few Cadets had trouble with this. We next taught formation takeoffs and landings (formation landings were later terminated as being too dangerous). We taught night flying and instrument flying. We also taught spins but they were also declared too dangerous. In subsequent classes, we also taught Cadets how to fly the AT-9 which landed at 110 to 120 mph and the English Avro-Anson, which was used to evacuate personnel from Dunkirk.

Our first Commanding Officer at Stockton AFB was of the “old school”. He always flew the AT-6 with the wheels down even though the landing gear was retractable. And he always wore a helmet and goggles, even though the aircraft had a closed canopy.

Since some of the pilots would become fighter pilots, we taught them air-ground gunnery. A large white target was erected on some vacant pasture land near Sacramento for target practice. During takeoffs we had to keep some right rudder trim in to keep the aircraft flying straight ahead. In air-ground you had to keep some left rudder trim in to keep the aircraft straight due to a lessened engine torque. So, a basic adjustment had to be made in air-ground gunnery.

A 30 caliber machine gun was mounted just ahead of the pilot so the firing had to be synchronized with the blades of the propeller. Since the engine turned the propeller about 2000 revolutions per minute (RPM), the machine had to be carefully adjusted to fire just after one propeller had passed the vertical plane and before the next propeller arrived. 2,000 RPM equated to a little over 33+ RPM per second and since there were 2 propeller blades the timing between the gun and the blade had to be about 15+ revolutions per second. Unfortunately the machine gun on my plane went out-of-synchronization with the propeller of my plane. The result was that I shot two holes in one side of the propeller which caused the whole plane to shake. It was a long bumpy flight from Sacramento to Stockton AFB with that damaged propeller! I thought I would have a crash landing. Luckily, the plane held together and we landed safely. So, now when my daughter asks me what I did in the big war I could tell her, “I almost shot down my own airplane.”

We spent a lot of time teaching how to make a forced landing but very little time teaching how to bail out of an aircraft. Some Cadets felt that since the aircraft cost about $25,000.00 and the US Government only paid $10,000.00 for each pilot lost, it was a savings to the government if we brought the aircraft to earth. The successful landings would allow the aircraft to be repaired. Some of my classmates that went to North Africa had their first flights in P-40’s in combat. I was told that when these pilots were shot down, they did not know the proper bail out procedures. They were dragged across the dessert in their parachutes because they didn’t know how to spill the air out of their parachutes!

Instructor pilots flew with their Aviation Cadets for half a day. The Commanding Officer thought we were getting by too easy. So on our half day off, we were assigned additional duties. First I was made an assistant in the Motor Pool and monitored their activities. Then I was made assistant Squadron Commander for a Negro unit. There were two white officers and about 30 colored men. I was only in the unit for a few weeks and did not participate in their activities. The first Sergeant, one of the biggest men there, was about 6’4” and 250 pounds. There were no disciplinary problems there. These additional duties only lasted until we received a new Base Commander!

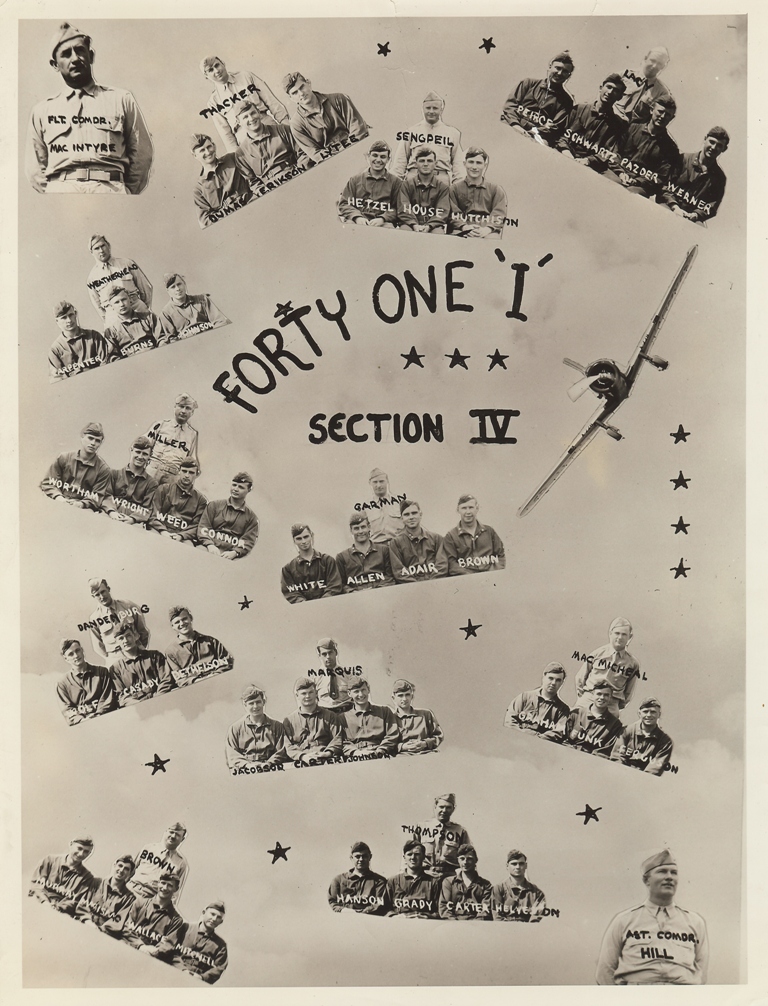

Here are some photos of Ray's students at Stockton. If you have any more information or the complete names of these gentleman please let us know.

Due to the critical need for more pilots and airplanes, many new pilot training airbases were activated in 1943. During the spring of 1943, I was transferred from Stockton AFB to Ft. Sumner AFB near the Pecos River, Albuquerque and Roswell in New Mexico. At the same period of 1943 many other airbases were started. Ft. Sumner AFB had been used to train glider pilots. Now the need for pilots of fighter and bomber aircraft was critical. The US and its allies were still on the defensive!!

To show the result of such increase in airbases, at Stockton AFB I trained five new pilots every three months. At Ft. Sumner, I was promoted to Squadron Commander where I was responsible for 10 instructors each with five Aviation Cadets, for a total of 50 new pilots. This ten-fold increase in pilots coupled with a corresponding increase in airplanes, allowed the US and its allies to overcome the advantage that Germany and Japan had during the first 2 years of WWII.

Pilot training at Ft. Sumner was conducted in the UC-78, which was a fabric covered aircraft over a metal frame. In the UC-78, the aviation Cadet sat in the left seat, while the Instructor sat in the right seat of a side by side configuration. This training was specialized for future bomber planes, where the pilot sat in the left seat and the co-pilot sat in the right seat.

Aviation cadet training for bomber pilots consisted of soloing in the aircraft, formation flying, instrument flying and night flying. There were no spins or air-ground gunnery. The UC-78 was stable and landed easily, so training was easier.

I was Squadron Commander at Ft. Sumner for about one year. In 1944, the need for pilots and aircraft lessened. So, during the next year to year and one half, several training bases were shut down. The increase in the number of planes and pilots, the increase in airplane performance, and the battles that US and its allies were now winning, changed the air battles from defensive to offensive! Fewer pilots were being killed and fewer planes needed to be replaced. The increased performance of these newer aircraft played an important part in lowering our losses. We were starting to win the war!!

When Ft. Sumner ceased its training mission, I returned to Stockton AFB where I was placed in charge of the WASP (Women’s Air Service Pilots). All these women were volunteers and were paid a monthly wage. Their job at Stockton was to test airplanes that had undergone minor/major maintenance to be sure they were safe for the Aviation Cadets to fly. The WASP’s were good pilots and, in the few months that I was their Commander, they did not have a single accident. They had the aircraft checked out on time and they were there every day. There were about 15-20 pilots who had undergone training at their airbase in Texas. One of our WASP’s was the daughter of a millionaire, so her pay was not important. She wanted to do her share in the WWII efforts. Sadly, even though the Wasp’s were successful, the entire program was terminated in 1944 because the male pilots were not happy with the female pilots-a mater of ego! And, of course, in late 1944 the numbers of male pilots were more than adequate for war needs.

During the later part of 1944, with the termination of the WASP program, I was transferred to Marfa AFB, Texas. About that time, I was placed on non-flying status due to a hearing problem. The noise of the aircraft, particularly the B-25’s, affected my hearing. I had a hard time even talking to my wife after flying. A hearing problem was relatively new at that time. The various Flight Surgeons were not familiar with the hearing problem. So, they tried various remedies-all unsuccessful! They removed two of my upper eye teeth under the theory that teeth and hearing were closely related. This solution to a hearing problem did not help! Since I was now a “grounded” pilot, I was made a Personal Affairs Officer and I was in charge of the War Bond drive at our base. We were successful in becoming No. 1 in the Western Division of the Flying Training Command. I was not happy with the non-flying job!

After several months at Marfa AFB, it was closed since the war effort by the US and its allies was now even more successful. Since my hearing problem was now lessened by not flying for several months, I was placed back on flying status. I was transferred to Nellis AFB, Nevada, where I now was scheduled to go overseas as part of the invasion force of Japan. I finally left Las Vegas AFB where qualified pilots were training in B-24s, preparatory to going overseas. During that period, every Friday for about three months, a B-24 crashed on takeoff. During takeoff, if you lost an outside engine, it required the full strength of both the pilot and copilot to keep the plane straight. During takeoff, it was critical not to suffer the sudden loss of an engine. This problem caused us to lose several planes and pilots. A lot of pilots were superstitious and didn’t want to fly on Fridays.

Finally, I got aboard a ship headed for the Orient in August 1945. We were part of the invasion force of Japan. I was about half-way across the Pacific Ocean, when the atomic bombs were dropped, and Japan finally surrendered. There has been much conversation about President Truman’s decision to drop the bomb but I, for one, was very thankful. Our ship took us to Leyte in the Philippines, where we disembarked. I was flown to Nielson Field in Manila, Philippines where I underwent training in off-loading and loading planes flying between Philippines, Okinawa and Japan. At this time Gen. Mac Arthur was in Japan in charge of the rehabilitation of Japan after their surrender. There were many C-47 & C-46 transport aircraft leaving the Philippines fully loaded and the returning from Japan empty.

I was next transferred to Naha AB, Okinawa right after a hurricane wiped out most of the permanent facilities and buildings. At this time, most of the planes were leaving the Philippines loaded with tents and rations for Okinawa. I had a force of about 20 Airmen to unload/load the aircraft. The allocation of tents and food was controlled by the US Navy. So, I went to my Navy representative to get tents and rations for my men. The Navy Commander could not find my small force on his list, and told me that he couldn’t help us. So I had my men taxi the next plane to our area, and we off-loaded all that we needed.

Now that the war was over, everybody wanted to go home so a point system was established to determine priority. I had enough points so that I could go home in January 1946. I came by a Dutch ship. The food was excellent, and I was happy to be coming home.

My first states-side station following the war was Santa Ana AFB, CA. I was quickly transferred to Kearns AFB, Utah. With the large number of men coming home, there had to be a source of replacements. Our processing center filled that need. I was in charge of many specialists: doctors, supply personnel, personal affairs, etc. We processed about 100 airmen per day to get them ready to go overseas. At that time, airmen could volunteer for Europe, Asia or “Undecided”. I had the dubious pleasure of telling them that if they volunteered for “Undecided”, the Air Force would send them to Asia! They were not very happy with me! Air Force officers were offered three choices for their future: 1. get out of the Air Force as soon as possible; 2. get out as of December 1946; or 3. stay on active duty. I chose option 2, and was released from the Air Force in December 1946.

Now that I was no longer in the Air Force, I had to make a living for my family and myself. I could have gone back to Sears Roebuck & Co. as shipping Manager in San Francisco, but I decided to see what I could do otherwise. I tried various odd jobs without success. Finally, I became the Manager of the California Department of Employment at Pittsburg, CA for about two years. I had two employees working for me, and we employed a lot of people-about one thousand in one year. But I had to take two outside jobs to make a living. I worked part time (after normal hours) as a janitor at the CA Dept. of Employment, and I worked as a salesman at the Western Auto in Vallejo, CA. Since the pay as Manager was only $300.00 per month, I decided to try elsewhere.

I changed jobs and became a full time employee of the CA Air National Guard in Oakland, California. I was happy with the work and the pay was better. I worked here for about three years. In fact, I probably would have continued there but for the Korean War. I received a telephone call in May 1951 from an USAF Colonel in the Pentagon. He said “Would you like to get called to active duty with our unit, or would you like to come to the Pentagon and work for me?” I asked him what I would be doing and he told me that I would be budgeting for about 10,000 full time Air National Guard employees like myself. I would also be defending that budget (about $35,000,000.00 per year) before budget committees and the Congress and then allocating the monies to the 50 states. I would also tour the Air National Guard units being called to active duty to see if they were properly manned and equipped to enter into the Korean War active force. I asked whether I would be on flying status. He said,” No,” so I said “I’m not interested.” He told me he would call me back the next day. He did and the job was with flying status. So I agreed. My pay would be doubled!

I spent four years in the Pentagon and had no trouble with the position. Toward the end of my tour I learned on my own, although it was not part of my job, how to budget for all the Air National Guard (ANG) personnel in the 50 states. The budget of all the ANG personnel was about $100, 000,000.00.

When my new boss came in (a full Colonel), he told me he had no idea how to prepare this budget. So, I told him that I would help him. When this budget came up, the Colonel and I spent about one week by ourselves predicting how many ANG people would join the units. My prediction was about 90,000. A budget analyst asked me what I would do if too few enlisted. I told him we would start a recruiting campaign. And sure enough, next March 1954, we were considerably short of the predicted and budgeted figure. So, the front office (two-star General) prepared a recruitment letter to the 50 State Adjutant Generals. When I received the letter, I had them change the recruitment completion date. Luckily, the changed date made the difference and everyone was happy.

The Colonel who had recruited me to the Pentagon gave me my choice of my next assignment as a reward. I knew that there was an overage of pilots so, to insure my future in the Air Force, I picked a category that was in short supply; Communication-Electronics. I had no background or training, so I was sent to the University of Maryland for two years to study electrical engineering. At the end of two years, I had the highest grade level of over 20 Air Force Officers in the courses.

I went to the Pentagon to check my next Air Force assignment. They said since you have been in a “soft-assignment,” now you get a rough assignment! My next assignment was a South Korean unit at Kangnung AB at the end of the supply chain in an isolated area. My job was as Commanding Officer of an airbase, a radar unit and a radio relay unit. I was responsible for 1,000 men (400 Air Force officers and airmen and 600 South Korean officers and enlisted men). Now that the Korean War was over, our primary mission was to train the South Koreans to operate the facilities with minimal help from the USAF. The training had been underway for a year before my arrival. I soon found that the USAF officers and men were prejudiced against the capabilities and knowledge of the South Koreans. I embarked upon a two pronged attack of the problem. I had the USAF officers and airmen stand back and let the South Koreans do the necessary tasks and I made a point of requiring personal and social contacts between our two groups. About ten months after my arrival, the South Koreans were ready. I had reduced the USAF personnel from 400 to 60. The South Korean government was very proud to be the first Asian unit to assume full control (especially to beat Japan) and they called me to Seoul, to award me an honorary set of Korean pilot wings. During this time, I was promoted from Major to Lt. Colonel.

Upon return to the US, I was assigned to the second SAGE unit in the US at Fort Lee Army Base, Petersburg, VA as a Communications Electronics’ Officer. We had the huge new IBM computer, along with five radar sites, ten communications sites and four air bases in our sector. I went to the first SAGE center in New York to find out what they were doing and how they were doing it. Unfortunately, the NY SAGE center was not operational and they couldn’t help us. So, we resorted to using what we considered to be a “common sense” approach.

The inspector rated our C & E unit as “outstanding” in our first operational exercise against theoretical enemy aircraft. I stayed at the Semi-Automated Ground Environment (SAGE) unit until May 6, 1961. My position was Director of Communications & Electronics. I supervised about 10 officers, 40 airmen and 7 or 8 contract agencies with 100 personnel. I also briefed the Air Staff and the contact personnel weekly. In addition, we had at least one briefing of USAF key personnel once each month. Luckily, it was not a problem for me to brief many differing types of people.

I then went to the Communications Electronics course at Kessler AFB to get additional training in my Air Force specialty.

From Kessler AFB, I was transferred to the Strategic Air Command at Offutt AFB in Nebraska as Chief of the Technical Support Branch at their Command level. I was responsible for planning, implementing and supervising Communication and Electronics (C& E) Systems for SAC throughout the world. My indirect supervision included about 6,000 personnel throughout the world. The C& E systems included a new computer system and the Atlas, Titan and Minutemen Missile Systems. There were too many miscellaneous C & E systems to mention. Needless to say, many of these systems were new and unique. Amongst these were the Minuteman Missile hardened cable systems. The cost per mile of the hardened cable was so expensive, that we had to run each cable directly in a straight line from each missile control center to each missile silo. This meant cables went through farmers’ yards and buildings and through lakes and rivers. Each few miles there were splice cases connecting each cable length to keep out water moisture. These splice cases had to be replaced, so contracts were let to buy new cases. C & E personnel had to replace these cases in ice, snow and rain. Again, “common sense” had to prevail. Even the telephone companies couldn’t help us, since they had not experienced such problems.

During my SAC tour I had to go to the Pentagon twice, once to resolve maintenance problems and once to get technical data, support and vehicles for C & E personnel at the missile sites. Another problem was that Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) sets were needed at each missile silo to protect against sabotage. The CC TV sets were purchased without technical data or supplies. So, I went to the Pentagon and received one million dollars to purchase the technical data and supplies.

There were also many contracts to various manufactures for maintenance help in various C & E systems throughout the world. Such contracts were loosely written and quite expensive. I was able to reduce the cost of these contracts by about 50% resulting in the saving of many millions of dollars. And with my computer experience in SAGE centers with large computers, I was a key individual in starting a new SAC computer system throughout the US and world. I was in SAC for four years.

From SAC, I was transferred to the FAA Headquarters in Washington, DC, as a liaison officer between the Hq USAF and FAA HQ. My job was to resolve any problems between USAF and FAA. They were jointly using many types of radar throughout the US. I was told not to wear my USAF uniform (a first) and to do what made “common sense” to help the US. The term for my work was “Joint Duty.” I recorded and resolved problems between these two agencies in quarterly meetings throughout the US between the FAA and the USAF representatives. I also helped generate a joint publication on the resolution of difficulties between the two agencies.

The USAF had an excellent retirement plan-50% of active duty basic pay after 20 years of service, and 75% of active duty pay after 30 years. The USAF permitted you to retire in the last pay grade, if you had held that job for two years. I had received a promotion from Lt. Col. to Full Colonel at the beginning of my joint tour so I had three years of duty as a full Colonel and could retire at that rank. I had no desire to become General. It was too political and I am not a good politician. Since I was only 50 years old in 1968 I could still enjoy new employment using skills and knowledge acquired in the military. And the retirement pay would last as long as you live. And, I assure you that pay from both military retirement and civilian employment at the same time after retirement, is sure nice.

When I retired from the USAF at age 50, I was too energetic to not do something useful. So, I went back to work. I had just completed my Master’s degree in Science Teaching at American University, Washington DC on my own, so I had additional credentials to assist me in landing civilian employment. I first tried teaching high school physics but quickly became disillusioned. My monthly pay was only $400 per month and I was working 80 hours per week. In addition, I had other unpaid duties such as the Chess Club advisor during my lunch hour. I also was an unpaid monitor at high school dances and sports events at nights and weekends. I quit after one semester. I regret that I was not able to pass on my knowledge and experience to the students

I was fortunate to find a position that was a perfect fit at Hughes Aircraft Co. as a design engineer for our defense systems and air traffic control systems. For the last two years of my 14 years at Hughes Aircraft Co., I worked as a consultant.

I have tried to show that you can serve in the USAF as a pilot, or in a non-flying capacity. I enjoyed both types of positions. Although it is a long way from hoeing sunflowers and corn in Nebraska to a full Colonel in the Air Force, it can be done, if you wish. I whole heartedly recommend a career in the Air Force. I found some lifelong friends in the Air Force; I enjoyed the growth in responsibility and positions, and I found, out that “common sense” applies everywhere.

Ray entered the Air Corps in April 1941 at Fort Stockton, CA graduating as a pilot December 5, 1941. During WWII he served as a flight instructor and also in the Pacific Theatre in the Philippines & Okinawa. From 1946-1951 he was a full time employee of the CA Air National Guard in Oakland, CA. Rejoining the AF in 1951, he served in the Pentagon and earned a degree in Communication-Electronics from the U. of MD. Ray’s next assignment was in South Korea. His unit at Kangnung AB was the first to be turned over to South Korea Upon returning to the US he served at Fort Lee, Petersburg VA as a Communications Electronics’ Officer, staying as Director of SAGE until 1961. He then transferred to Strategic Air Command at Offutt AFB, NE for four years and completed his career in Washington, D.C. as a liaison officer between USAF & FAA. He received his Master’s Degree in Science Teaching from American University in 1968. His last position was working as a design engineer for our defense systems for Hughes Aircraft Co., Fullerton CA.

Ray is predeceased by his two brothers, Eugene Wolf, who died in WWII at the Battle of the Bulge & Leonard Wolf. His first wife of 42 years, Dorothy Mildred McKay, died January 29, 1984. He is survived by his second wife of 25 years, Ruth Maxine Vosburg, his brother, Lindy of Arcata, CA, two daughters, Rita A. Pierce of Holden, MA and Ora Jean Wolf, three stepsons, Andre Gervais, Vern Gervais and Mark Gervais and twenty-six grandchildren & great grandchildren.